Banana Blossom Salad – Cheap Dinner Idea!

Home grown cheap and easy recipe

Last orders sent out Dec. 16th! You can still place orders, but they won’t be sent out before Jan. 6th. Merry Christmas!

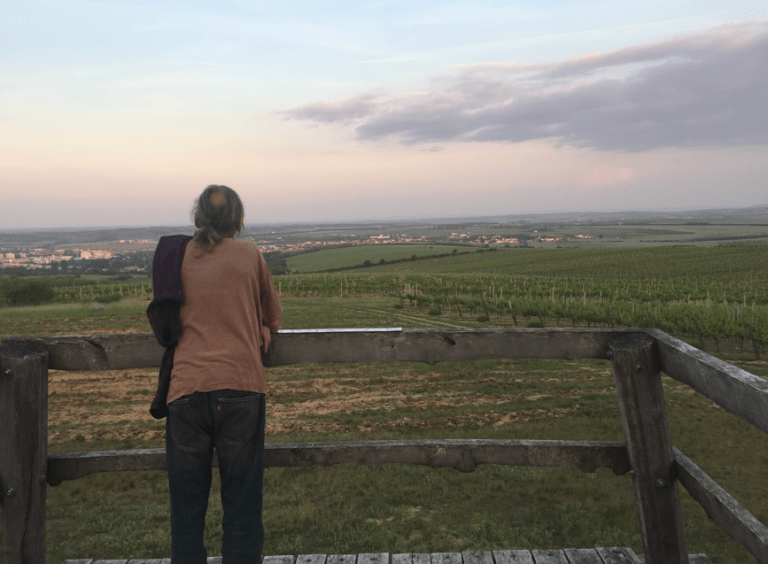

If you want to use your land successfully you need to understand your land. One of the basic things to consider is its shape. Why is the shape of the land so important?

The first thing that comes to mind is water.

Steep slopes lose water fast, flat land holds water for longer. Tops of the hills or ridges quickly become dry, lower parts of slopes receive water from the higher parts.

At the lowest places in landscape there are watercourses, creeks, lakes and rivers, prone to water erosion and inundation.

The second thing that comes to mind is sunlight. In Australia, the north facing slopes are warm, dry and sunny, while the south facing slopes are the opposite – shady and cool. Steep mountains shade the valleys between them. Go to your land and observe how it is shaded. Do it at the time of summer and winter solstice.

Last but not least – tops of the hills have stronger winds, valleys are sheltered. Also, cold air flows down – on a frosty night, the bottom of the hill gets hit the hardest.

Why not to leave your land just as it is? Natural ecosystems can have fertile patches that naturally collect organic matter, are water retentive and do not flood.

Areas like this occur randomly and are relatively rare. In your ecosystem, you will probably need to change the shape of the land to create the best conditions.

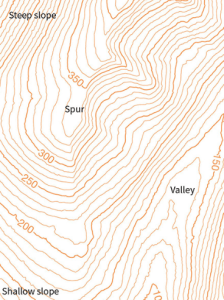

Contours are imaginary lines which connect places of the same height. The shoreline of a lake, for example, however winding, is a contour. If you would drain the lake so that the surface is 5 m lower than before, you would get a new shoreline, another contour, and so on.

Contours are commonly visible on topographic maps. The closer they are to each other, the steeper the slope.

The best maps for you are the topographic maps from the Spatial Services of the NSW Government (I guess other states have something similar) which come in hard copies or in a downloadable form and also “sixmaps” https://six.nsw.gov.au/ which are only online.

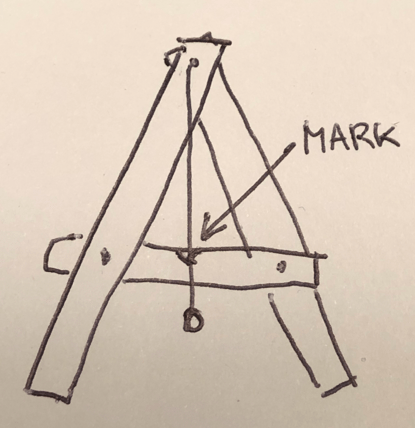

How do you measure contours? The most simple way is with a timber A-frame, which you can build yourself. Fix a string so that it hangs from the top with a weight at the end. Mark where the string crosses the middle bar when standing on a level ground. Then you can “walk” the A-frame across the slope in such a way that the string is always on the mark i.e. horizontal. Every “footprint” marks the contour line.

Another way to measure contours would be with a long hose filled with water. The hose should be clear at least at the ends so that you can see the water inside. Needles to say, it’s cumbersome and you will get wet. It can give you a good indication about the fall of the slope, however, if you use a measuring stick at the lower end.

If you love modern gadgets, there are some good laser tools used by builders. The most accurate tool, of course, is the theodolite.

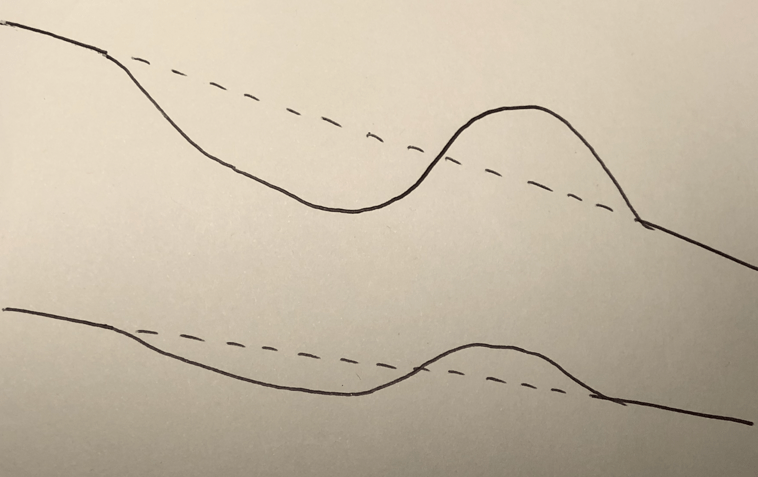

It’s a good idea to slow down the flow of water on slopes so that it has time to infiltrate deeper into the soil before running off. To do this, you need to build swales or terraces.

If you dig a shallow trench along the contour (throw the soil down the hill to create a mount), the water inside will not flow anywhere. This is called a ‘swale”. It can be as long as you wish, however, it’s hard to keep it perfectly level on longer distances.

Swales are often used in permaculture. The benefits are obvious. There is a moist zone at the bottom which gradually accumulates organic matter and encourages deep water penetration, and the zone at the top of the swale which has always perfect drainage, even on heavy soils. A swale will fill with water after a heavy rain and the water usually soaks in within some hours. Swales should be not overloaded with too much water so they should be made at regular intervals.

Terraces can be as simple as a low stone wall or old logs arranged along the contour backfilled with soil or organic matter. Or, they can be carefully levelled with a raised edge to hold water as in the Asian rice fields. The young rice is planted at the beginning of the rains and the standing water suppresses weeds. It has to be very carefully calibrated to the amount of rain, otherwise once one terrace breaks, the whole hillside underneath just slides down.

In Australia, drought proofing your property is essential. You can harvest water from roofs into the water tanks and you can also harvest water with drainage channels and dams.

Harvesting water from roofs is simple. If you have 5 x 4 m roof and you receive 5mm of rain, you will get 10 (40 x 50 x 0.05 dm3) litres of water.

Estimating a harvest from the land is much more complicated. Runoff water is not all the water that falls from the sky like on the roof. Some of the moisture will soak into the soil until saturated.

Every dam has a catchment area that feeds it. If you want to calculate the size of it, you need to find a teenager who completed HSC in the past two months. They still know how to calculate irregularly shaped areas. As a second best, try to superimpose a rectangle or triangle shape over the catchment so that you can calculate it yourself.

You can simply put a dam anywhere in the lower lying part of your land. If you look at Google maps you will see that’s what everyone else is doing.

Or, you may want to maximise your water harvest. On this topic you can’t go past Percival Alfred Yeomans. His book The Keyline Plan from 1954 is a classic.

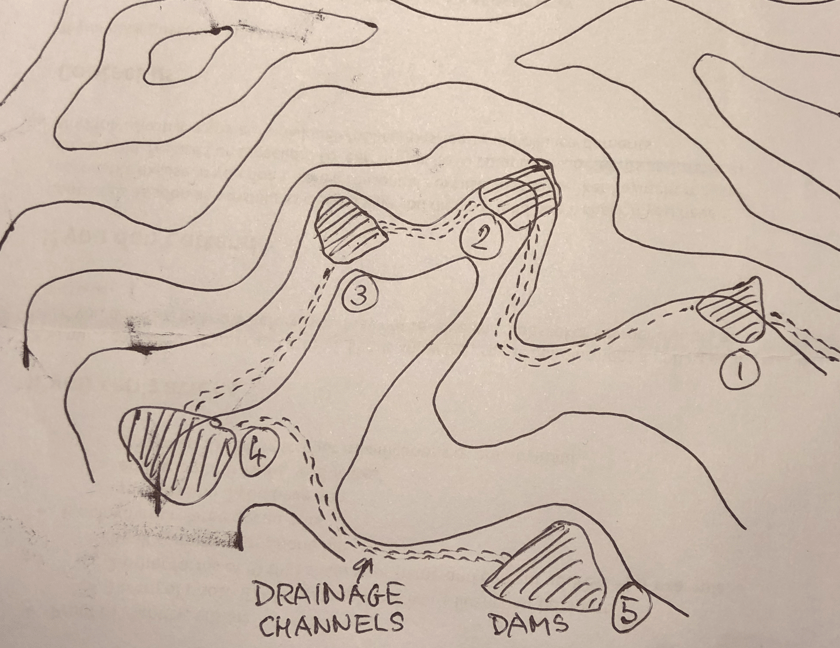

In a nutshell, you can build a system of drainage channels and dams starting up close to the ridge. The idea is to catch the water as high on the slope as possible. The overflow of each dam goes nearly along the contour (you try to enable flow without causing erosion) towards the next dam, lower and lower. If you need to, you can continue to the lowest point of the property.

The beauty of this system is a maximum water retention, minimal erosion and some of the stored water is high up on the slope, so you can use gravity for easy irrigation.

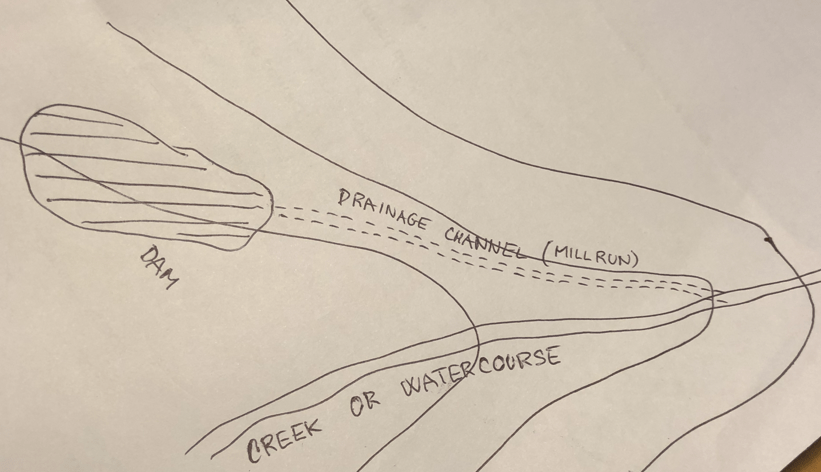

Yeomans keyline system is the best system for people whose property is in the upper catchment. If you are further down the hill, you may have a creek or watercourse you could harvest water from. If the catchment area is large, you can’t dam the creek directly, the amount of water would break the dam wall or silt it.

What you could do in such a case is a “mill run” – a feeding canal that brings water whenever it rains, but only a limited amount. The channel starts at an elevation of several meters up stream, it takes some water from the main stream, and it carries it nearly along the contour to the dam, which is a few meters above the creek. The levels are designed so that the feeding channel stops flowing when the dam is full. Hence, no siltation.

All these things have to be considered and done first, before planting anything. It will pay off thousand fold in the future. This is the heart of abundance. Water. Not too much, not too little.

Water brings nutrients, water supports life.

Share:

Home grown cheap and easy recipe

I switched from in-ground to raised beds and this is what I found.

Why to embrace weeds in your edible landscape!

The best way to understand how the water flows on your property is to put on the gumboots and a raincoat and walk on your